A group of kids stand around a hole in the ground. As you interact with the scene, they start to take a dive. They fall in as a group, until the hole is the only thing left on the screen. Just looking at this scene, it would seem that Kids, the newest game from Michael Frei and Mario von Rickenbach, is asking a variation on the old question that parents ask children: “If all your friends jumped off a bridge, would you?” But there’s one big difference. In Kids there is no “you.” You play as the collective, controlling all of the titular children.

This hole in the ground is returned to again and again in Kids, and it can be read multiple ways. It can be seen as a meditation on peer pressure and how people are lead to do destructive things through the destructive acts of others. In that way it is about the danger of the collective, hewing closely to the parental warning about bridges and following friends into destructive actions. It can be read as an absurd gag, supported by the goofy animation. Watching these kids hopelessly flop into a hole is hilarious as long as we don’t think about it, at which point it becomes so depressing that we might have no way to face it other than with laughter. As Frei told Andrew Webster of The Verge, “Some see it as something dark, some find it hilarious.”

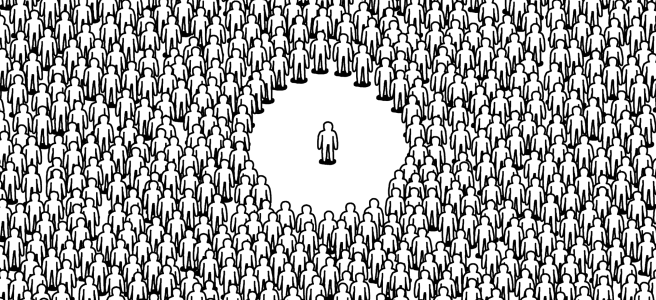

Regardless of your reaction, Kids is clearly about collectives and group dynamics. But, I agree with Jess Joho, who has written that Kids is not as negative a reflection on groups as it might originally seem. Even if there are moments when the collective might be dangerous or tedious, Kids understands that there’s power in a group, and that that power is not inherently bad. As Joho writes, “Kids insists on the beauty of being one indistinguishable part of the masses, part of something cosmically bigger than any one ego.” In the game, a lot of this beauty comes from the animation. As I write this, I’m watching tree branches swaying in the breeze, and I’m reminded of the way that the kids move. They don’t move with precision or purpose. There is no tension or the feeling like they “need” to do any of this. The motion is all carefree and easy. When standing around the hole, the kids don’t excitedly jump in or slowly lower themselves down. The simply put their arms to the side and shift their weight forward until the belly-flop into the abyss. It’s effortless and beautiful. You can choose which kids jump in the hole first by clicking on a certain part of it, and when I did it I dragged my mouse around the circle like a clock to make it look like a synchronized performance. There’s no strategy to doing this, but I liked the aesthetic.

But not all of the aesthetics in Kids are that calming. The kids running across the screen is similarly fun, but also overwhelming, like a herd of animals. This is no doubt helped by the loud footstep sound effects that overpower these scenes. And then there’s the group of kids so large that they fill up more than the space of the screen, who clap on command and with synchronicity. This clap is impressive and awe-inspiring, but it’s also a little scary. It feels a lot less playful than the dive into the hole. The rigidness and perfectness of it gives it a military feel.

The contradiction between these different moments of collectiveness is a good thing. Kids is representing the wholeness of collectivity, not just one selected part of it. A collective can be beautiful, powerful, relaxing, terrifying, etc. As Joho says, “there is something equally beautiful (a synchronized dance performance) and disturbing (a Nazi rally) about the power of what happens when human beings act as one.”

But the larger point in Kids is that we only accomplish these things when we act as a group. An individual, when faced with a collective, is powerless. And whether that is a good or bad thing, that is the truth of the world we live in and one that we have to learn to handle.

It’s a truth that is perhaps most important when we choose to go against the collective, because it reminds us that we need a collective of our own to do so successfully. There are attempts to go against the collective in Kids. One of these involves a small group that explores the depths of this journey through the hole in a way that the larger collective never does. This smaller group swims up-river (literally and metaphorically) and discovers something new and beautiful. Once they do, they sing a song together, one that is more asynchronous than the collective clap. Their song causes more kids to join them. It’s a rejection of the clap and allows more room for the personal due to its asynchronicity, but it is still collective, still collaborative. The parts might be more individualized, but they are still creating a whole. These are competing ideas of what a collective can look like, but they draw their power from the same place.

Kids has one character that acts purely as an individual. (And even then, if we want to try and connect some abstract scenes, we might be able to assume that they were forced to act this way by a collective). Either way, when this child falls into the center of the clap, they are terrified, and they run. They run through the crowd, across multiple distinct screens, and there are no attempts made to stop them. Other kids just stand to the side and let them through. This kid eventually reaches the screen with the hole and collapses, exhausted from all the running. With nobody around to help them, you, the player, are allowed to act as the hand of nature and drag them into the hole, returning them to the cycle they were trying to escape. The world takes its toll on an individual, and when it does, there is nobody around to offer help.

It would take a superhuman effort to single-handedly resist the collective, and we’re just a bunch of kids. But together, not only can we change the world, but we are always changing it, for good or for ill.